Al Contributed a Painting to the Metropolitan Museum of Art of St Louis Missouri

| Albert Hirschfeld | |

|---|---|

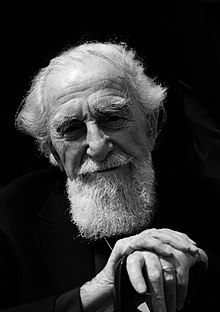

Hirschfeld in 2000 | |

| Born | (1903-06-21)June 21, 1903 St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died | January 20, 2003(2003-01-20) (aged 99) New York Metropolis, New York, U.S. |

| Education | Art Students League of New York |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 1 |

Albert Hirschfeld (June 21, 1903 – January twenty, 2003) was an American caricaturist best known for his black and white portraits of celebrities and Broadway stars.

Personal life [edit]

Al Hirschfeld was born in a ii-story duplex at 1313 Carr Street[1] in St. Louis, Missouri, and afterwards moved with his family unit to New York City, New York in 1915, where he received his art training at the National Academy of Pattern.

He married chorus daughter Florence Ruth Hobby in 1927,[two] separating from her in 1932, and the ii were divorced in 1943. That same twelvemonth he married actress/performer Dolly Haas. Haas died from ovarian cancer in 1994, anile 84. They had i child, a daughter, Nina (b. 1945).

In 1996, he married Louise Kerz, a theatre historian (b. 1936).[iii]

Career [edit]

In 1924, Hirschfeld traveled to Paris and London, where he studied painting, cartoon and sculpture. When he returned to the United states, a friend, fabled Broadway press agent Richard Maney, showed one of Hirschfeld's drawings to an editor at the New York Herald Tribune, which got Hirschfeld commissions for that newspaper and then, later, The New York Times.

Hirschfeld's mode is unique, and he is considered to be one of the most important figures in gimmicky cartoon and extravaganza, having influenced countless artists, illustrators, and cartoonists. His caricatures were regularly drawings of pure line in blackness ink, for which he used a 18-carat crow quill.[4]

Readers of The New York Times and other newspapers prior to the time they printed in color will be about familiar with the Hirschfeld drawings that are black ink on white illustration board. However, there is a whole body of Hirschfeld'south work in color.[5] Hirschfeld's full-colour paintings were commissioned by many magazines, often as the embrace. Examples are TV Guide, Life Magazine, American Mercury, Look Magazine, The New York Times Magazine, The New Masses, and Seventeen Magazine.[6] He also illustrated many books in color, most notably among them Harlem As Seen By Hirschfeld, with text by William Saroyan.[seven]

Liza Minnelli, Minnelli on Minnelli, 1999.[8]

He was deputed past CBS to illustrate a preview magazine featuring the network's new TV programming in fall 1963. One of the programs was Candid Camera, and Hirschfeld's caricature of the evidence's host Allen Funt outraged Funt so much he threatened to get out the network if the mag were issued.[ citation needed ] Hirschfeld prepared a slightly unlike likeness, possibly more flattering, but he and the network pointed out to Funt that the artwork prepared for newspapers and some other print media had been long in preparation and information technology was too late to withdraw information technology. Funt relented but insisted that what could be changed would take to be. Newsweek ran a squib on the controversy.[ citation needed ]

Broadway, flick, and more [edit]

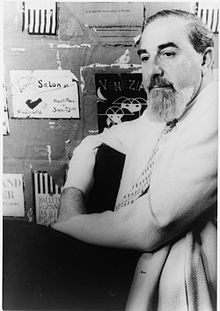

Hirschfeld started young and continued cartoon to the cease of his life, thus chronicling nearly all of the major entertainment figures of the 20th century.[9] During his eight-decade career, he gained fame by illustrating the actors, singers, and dancers of various Broadway plays, which would appear in advance in The New York Times to herald the play'southward opening. Though the theater was his best-known field of interest, co-ordinate to Hirschfeld's fine art dealer Margo Feiden, he really drew more for the movies than he did for alive plays. "By the ripe old age of 17, while his contemporaries were learning how to sharpen pencils, Hirschfeld became an art director at Selznick Pictures. He held the position for about 4 years, and and then in 1924 Hirschfeld moved to Paris to work and pb the Maverick life. Hirschfeld also grew a beard, necessitated by the exigencies of living in a cold water apartment. This he retained for the side by side 75 years, presumably because "you never know when your oil burner will go on the fritz."[10]

In addition to Broadway and motion picture, Hirschfeld likewise drew politicians, TV stars, and celebrities of all stripes from Cole Porter and the Nicholas Brothers to the cast of Star Trek: The Next Generation. He also caricatured jazz musicians——Glenn Miller, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Silly Gillespie, Billie Holiday, and Ella Fitzgerald—and rockers The Beatles, Elvis Presley, Bruce Springsteen, Bob Dylan, Jerry Garcia, and Mick Jagger.[11] In 1977, he drew the embrace of Aerosmith'south Describe the Line album.

Hirschfeld drew many original movie posters, including for Charlie Chaplin's films, as well every bit The Wizard of Oz (1939). The "Rhapsody in Blueish" segment in the Disney picture Fantasia 2000 was inspired past his designs, and Hirschfeld became an artistic consultant for the segment; the segment's director, Eric Goldberg, is a longtime fan of his work. Further bear witness of Goldberg'southward adoration for Hirschfeld can be found in Goldberg'southward grapheme design and animation of the genie in Aladdin (1992). He was the field of study of the Oscar-nominated documentary picture show The Line King: The Al Hirschfeld Story (1996).

Nina [edit]

In 1943, Hirschfeld married German actress Dolly Haas. They were married for more than fifty years and had a girl, Nina.[x]

Hirschfeld is known for hiding Nina'due south proper noun, written in upper-case letter letters ("NINA"), in well-nigh of the drawings he produced later her nascence. The proper name would appear in a sleeve, in a hairdo, or somewhere in the background. As Margo Feiden described information technology, Hirschfeld engaged in the "harmless insanity," as he called it, of hiding her name at least once in each of his drawings.[A] The number of NINAs concealed is shown by the number written to the right of his signature. Generally, if no number is to be institute, either NINA appears once or the cartoon was completed before she was born.[10]

For the commencement few months after Nina'south nativity, Hirschfeld intended the hidden NINAs to appeal to his circle of friends. Merely what he hadn't realized was that the population at large was beginning to spot them, too. When Hirschfeld thought that the gag was wearing thin amidst his friends and stopped concealing NINAs in his drawings, letters to The New York Times ranging from "curious" to "furious" pressured him to brainstorm hiding them again. He said it was easier to hide the NINAs than information technology was to respond all the mail. From fourth dimension to time he lamented that the gimmick had overshadowed his art.[10]

In Hirschfeld's volume Evidence Business is No Business organization, Feiden recounts the following story to illustrate what Hirschfeld meant when he referred to the NINA counting as a harmless insanity: "The NINA-counting mania was well illuminated when in 1973 an NYU student kept coming back to my Gallery to stare at the aforementioned drawing each day for more than a week. The drawing was Hirschfeld's whimsical portrayal of New York's Central Park. When curiosity finally got the best of me, I asked, 'What is so riveting nearly that i drawing that keeps you here for hours, solar day after day?' She answered that she had constitute only 11 of 39 NINAs and would not give upwardly until all were located. I replied that the '39' next to Hirschfeld's signature was the year. Nina was born in 1945."[ten]

In his 1966 anthology The World of Hirschfeld, he included a cartoon of Nina that he titled "Nina's Revenge". That drawing independent no NINAs. At that place were, however, two ALs and two DOLLYs ("the names of her wayward parents").[12]

In the Fantasia 2000 segment, the crimp of Duke the Builder'southward toothpaste tube contained a NINA in tribute to Hirschfeld.

Publications [edit]

Al Hirschfeld famously contributed to The New York Times for more than seven decades. His piece of work also appeared in The New York Herald Tribune, The Old Globe, The New Yorker Magazine, Collier'southward, The American Mercury, Boob tube Guide, Playbill, New York magazine, and Rolling Rock.

In 1941, Hyperion Books published Harlem As Seen By Hirschfeld, with text by William Saroyan.[13]

Hirschfeld'southward illustrations for the theater were gathered and published yearly in the books, The Best Plays of ... (for example, The Best Plays of 1958-1959).[14]

Additional collections of Hirschfeld'due south illustrations include: Manhattan Oasis, Bear witness Business Is No Business (1951), American Theater, The American Theater as Seen by Al Hirschfeld, The Entertainers (1977), Hirschfeld by Hirschfeld (1979), The World of Al Hirschfeld (1970), The Lively Years, 1920-1973 with text by Brooks Atkinson, Hirschfeld'south World (1981), Show Business organisation is No Business concern with preface and endnotes by Margo Feiden (1983), A Selection of Limited Edition Etchings and Lithographs with text by Margo Feiden (1983), Art and Recollections From 8 Decades (1991), Hirschfeld On Line (2000), Hirschfeld's Hollywood (2001), Hirschfeld's New York (2001), Hirschfeld's Speakeasies of 1932 with Introduction by Pete Hamill (2003), and Hirschfeld's British Isles (2005).

Hirschfeld collaborated with humorist S. J. Perelman on several publications, including W Ha! Or, Around the World in 80 Clichés, a satirical expect at the duo'due south travels on assignment for Holiday magazine. In 1991, the United states Mail commissioned him to draw a series of postage stamps commemorating famous American comedians. The collection included drawings of Stan Laurel, Oliver Hardy, Edgar Bergen (with Charlie McCarthy), Jack Benny, Fanny Brice, Bud Abbott, and Lou Costello. He followed that with a collection of silent pic stars including Rudolph Valentino, ZaSu Pitts and Buster Keaton. The Postal Service immune him to include Nina'due south name in his drawings, waiving their ain rule forbidding hidden messages in United States postage designs.

Hirschfeld expanded his audition by contributing to Patrick F. McManus' humour column in Outdoor Life magazine for a number of years.

Collections and tributes [edit]

Permanent collections of Hirschfeld's work can exist found at a variety of institutions including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the New York Public Library in New York, Harvard University in Cambridge, and the Harry Ransom Center in Austin, Texas.

Hirschfeld was the recipient of two lifetime accomplishment Tony Awards. On June 21, 2003, the Martin Beck Theatre on Broadway was renamed the Al Hirschfeld Theatre. Hirschfeld was too honored with a star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame.[15]

In 2002, Al Hirschfeld was awarded the National Medal of Arts.[16] He was an Honorary Member of the Salmagundi Club.[17]

Death [edit]

On January 20, 2003, Hirschfeld died of natural causes in his dwelling house at 122 East 95th Street in Manhattan.[xviii] He was survived by his daughter Nina Hirschfeld Westward, and his third wife, Louise Kerz.

See besides [edit]

- List of caricaturists

- Listing of Goggle box Guide covers

Notes [edit]

- ^ This practice has given rise to the term "nina", used by crossword puzzle writers and fans to refer to "a subconscious message revealed in the completed grid of a crossword".

References [edit]

- ^ Besser, Joe (1985). In one case a Stooge, E'er a Stooge. Knightsbridge Publishing. p. half dozen. ISBN1-877961-42-half dozen.

- ^ Shepard, Richard F.; Gussow, Mel (January 21, 2003). "Al Hirschfeld, 99, Dies; He Drew Broadway". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 11, 2017. Retrieved Feb 14, 2017.

- ^ "Louise Kerz and Al Hirschfeld". The New York Times. No. 27 October 1996. New York. October 27, 1996. Archived from the original on March four, 2016. Retrieved December 3, 2016.

- ^ Hirschfeld, Al. "Al Hirschfeld.com". Whatever Drawing on the Website. Margo Feiden Galleries Ltd. Archived from the original on May 4, 2013. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ Hirschfeld, Al. "Al Hirschfeld'south Early Color Portfolio". Hirschfeld's Early on Color Portfolio. Margo Feiden Galleries Ltd. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ Brian, Greg. "The Autumn of the Tv set Guide Empire". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on June xv, 2013. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ Hirschfeld, Al (1941). Harlem Equally Seen By Hirschfeld. New York: Hyperion Press.

- ^ Hirschfeld, Al. "Liza Minnelli, Minnelli on Minnelli". Margo Feiden Galleries Ltd. Archived from the original on November 12, 2013. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ^ The Hirschfeld Century: Portrait of an artist and his age, edited and with text past David Leopold, Knopf, 2015.

- ^ a b c d eastward Show Business is No Business concern (1983). New York: Da Capo Printing, pp. Endnotes, ISBN 0306762218

- ^ "Al Hirschfeld/Margo Feiden Galleries Ltd". Alhirschfeld.com. Archived from the original on January xiii, 2017. Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- ^ Hirschfeld, Al (1970). The Earth of Hirschfeld. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN0810901773.

- ^ Harlem As Seen By Hirschfeld Archived 2016-11-22 at the Wayback Machine, Manhattan Rare Books. Retrieved November 21, 2016

- ^ "The best plays of 1958-1959, ed. by Louis Kronenberger ; illustrated with drawings past Hirschfeld Archived 2016-11-22 at the Wayback Machine," Yuma County Library District. Retrieved Nov 21, 2016

- ^ "St. Louis Walk of Fame Inductees". St. Louis Walk of Fame. Archived from the original on 31 October 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ^ "Lifetime Honors: National Medal of Arts". Nea.gov. Dec 8, 2003. Archived from the original on December 8, 2003. Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- ^ "New York Architecture Images-Salmagundi Club". Nyc-architecture.com. November 24, 1937. Archived from the original on April 17, 2017. Retrieved Dec fourteen, 2016.

- ^ Gussow, Richard F. Shepard With Mel (January 21, 2003). "Al Hirschfeld, 99, Dies; He Drew Broadway". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

External links [edit]

- Al Hirschfeld Foundation (official site)

- Al Hirschfeld Papers at the New York Public Library

- Al Hirschfeld Collection at the Harry Ransom Heart

- Creative person proofs past Al Hirschfeld at the Margaret Herrick Library

- Exhibit: The Line King's Library: Al Hirschfeld at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts - Fall, 2013.

- Exhibit: Al Hirschfeld, Beyond Broadway exhibition at the Library of Congress

- St. Louis Walk of Fame

- Jewish American Hall of Fame

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Al_Hirschfeld

0 Response to "Al Contributed a Painting to the Metropolitan Museum of Art of St Louis Missouri"

ارسال یک نظر